Trustee Ben Cowell, Director General of Historic Houses, has provided this report about our annual symposium, which took place at the Galleywood Heritage Centre on Saturday 4 October 2025.

The Essex VCH Trust was very grateful to all who joined in our 2025 study day, held at the Galleywood Heritage Centre on Saturday 4 October. Our theme for the day was ‘Crime and Society in Essex’, and we were treated to four exceptional talks covering a range of periods and perspectives.

Simon Coxall began proceedings with an intriguing talk on the ‘Curious Quest for Quamstowe’, exploring judicial execution in medieval Essex. The term ‘Quamstowe’ referred to the gallows that served as the sites of execution for many manors and parishes. Simon had located over fifty such sites across the county, meaning that they might have been shared between several townships or settlements. For this reason, they were often located on administrative boundaries (which explains why they were so often found on hilltops), as well as at the intersection of major highways (often former Roman roads). The most famous gallows site in English history was Tyburn, located beyond the outer edge of Westminster and the city of London and at the intersection of two important Roman roads (Watling Street, and the road that is now Oxford Street). More research was needed to excavate more of the history of gallows sites in Essex, now entirely lost to posterity but nonetheless surviving as traces in field names and on maps.

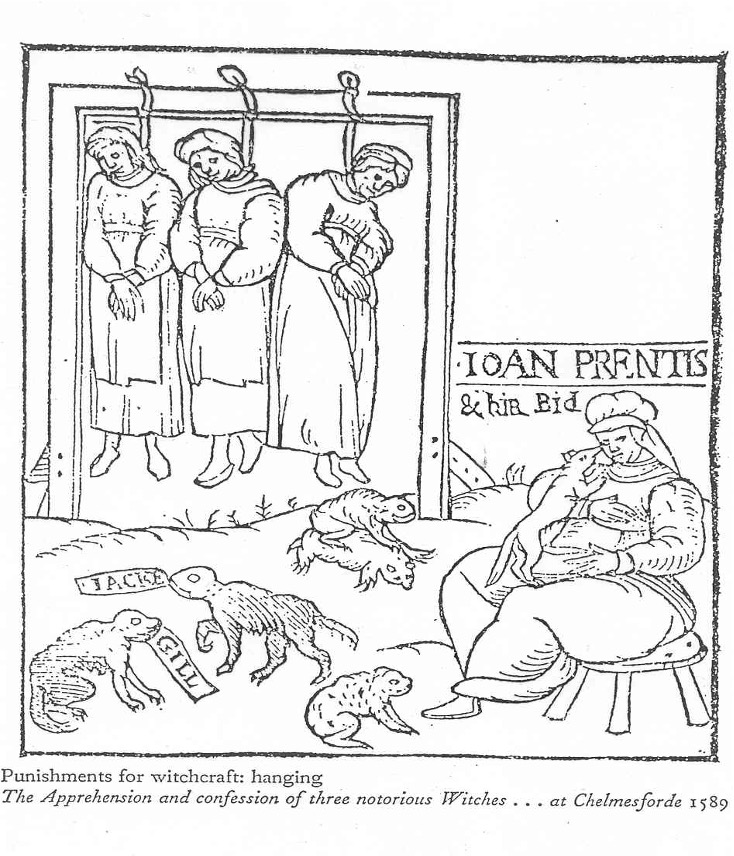

Next, Alison Rowlands (University of Essex) treated us to a bravura account of the witchcraft trials in Essex of the 16th and 17th centuries. Her principal focus was the surge in witchcraft convictions of the 1570s and 1580s, a prelude to the more famous spike in prosecutions that occurred in the 1640s thanks to Matthew Hopkins. Alison directed her attention away from Hopkins and towards the 16th-century convictions, asking why they grew in such number at this time. Answers were variously associated with factors such as harvest failures, misogyny, and the propensity of puritan elements to be especially damning of those believed to be acting in association with the devil and his familiars. Some men were convicted of ‘magic murders’, but witchcraft was predominantly a charge levelled at women, often those who were older and living alone. Essex was noticeable for the volume of its witchcraft convictions, and Alison convinced the room that much more historical research was needed on this most fascinating (as well as disturbing) of topics in English social history.

The conversation shifted another gear with our next speaker, John Walter (Professor Emeritus, University of Essex). John gave a masterful account of the moral economy of food protests, using examples from Essex in the 17th and 18th centuries. Claims of the ‘people’ often paralleled the viewpoint of the government, at least when it came to attitudes towards ‘Dunkirkers’ and other elements in the political economy of grain. The law did not recognise assemblies of women protesting against food prices as criminal, which gave legal cover for women in Maldon in 1629 to invade a ship sitting in the quay with a cargo of grain, bound for the continent. By demanding for their bonnets and the folds in their skirts to be filled with grain, these women were participating in a choreographed expression of moral attitudes towards the free market. They did not regard themselves necessarily as protestors, so much as providing a corrective to the worst excesses of capitalism at times of extreme hunger. Nevertheless their leader, ‘Captain’ Ann Carter, was eventually hung for inciting riotous behaviour.

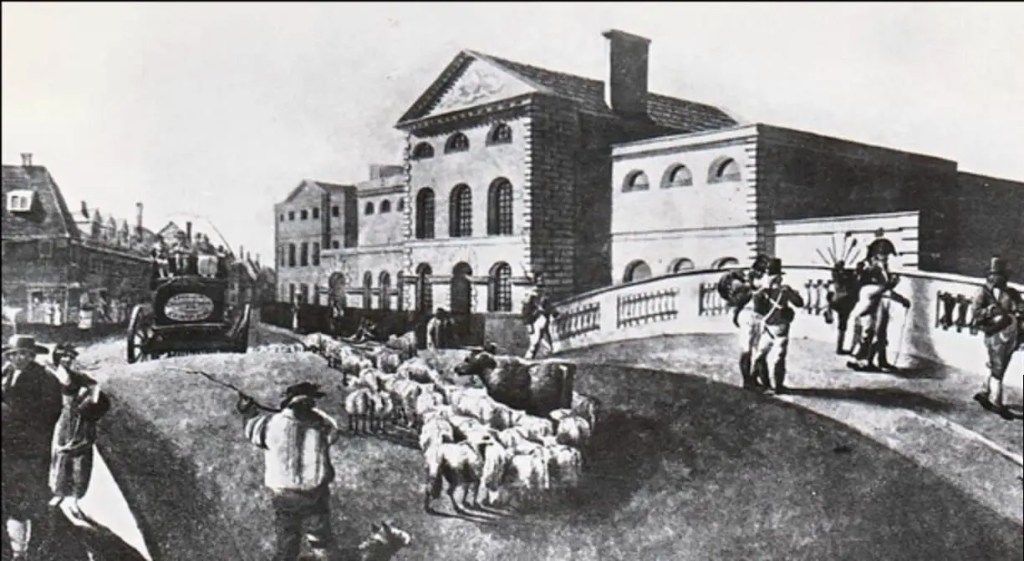

Finally, Jane Pearson (University of Essex) gave us an excellent overview of the workings of crime and punishment in Essex in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Using the example of a set of travelling performers and quack doctors (mountebanks) in Epping in 1791, she invited us to speculate on the criminality or otherwise of these sorts of gatherings. The crime at stake here was not necessarily that of performing without a licence, so much as of running a lottery (open-air gambling games). Several of the protagonists ended up spending time in Chelmsford goal. This itself was an indication of changing attitudes towards crime, with incarceration reinvented in the 19th century as first and foremost a means of punishment. Although prisons at this time were not pleasant places, it at least meant that judges were making less recourse to the gallows – which had by now ceased to be the ubiquitous features in the landscape that Simon Coxall had described earlier in the day.

The four talks sat well together, and several themes emerged. One was the exceptionalism of Essex when it came to particular crimes, such as claims of witchcraft or some types of food riot. Another theme was the role of women, both as the victims of crime but also as agents of protest and extra-judicial action. We extend our thanks to all our speakers, as well as to our audience for their intriguing questions and comments throughout the day.