As we continue planning for this year’s annual symposium at the Galleywood Heritage Centre on Saturday 4th October, a look back at last year’s event!

We were grateful to three of our trustees, Lord Petre, Dr Amanda Flather and Sir Graham Hart for giving talks, alongside our long-term friend the architectural historian Dr James Bettley. In this blog chairman Ken Crowe provides an overview of each of their talks.

Lord Petre: The Catholic Experience in Essex, 1535–1829

It was clear that throughout this three-hundred-year period, Catholics of great skill and abilities were able to rise to high office. William Petre, one of the king’s commissioners for the Dissolution of the monasteries, continued to hold high office into Elizabeth’s reign. John explained that, despite the high price paid by some, it was really only after the excommunication of Elizabeth by Pope Pius V that Catholics in general began to suffer from a series of draconian laws. But even then, when Catholic priests were regarded as enemies of the state, others could rise to the top. John cited the example of William Petre’s son, John, who was commander of the Essex Militia at Elizabeth’s Armada speech at Tilbury.

The practise of Catholicism was banned, and anybody not attending (Protestant) church was to be summonsed, such as the Ingatestone widow and her daughter who were fined £120 in 1621. The second Lord Petre’s sons were arrested in 1627 for attempting to go abroad to attend a Catholic school. Catholics were also excluded from the professions or dealing in property. By an Act of 1700 Catholics were not allowed to go more than 5 miles from their usual place of abode, or to own a horse worth more than £5!

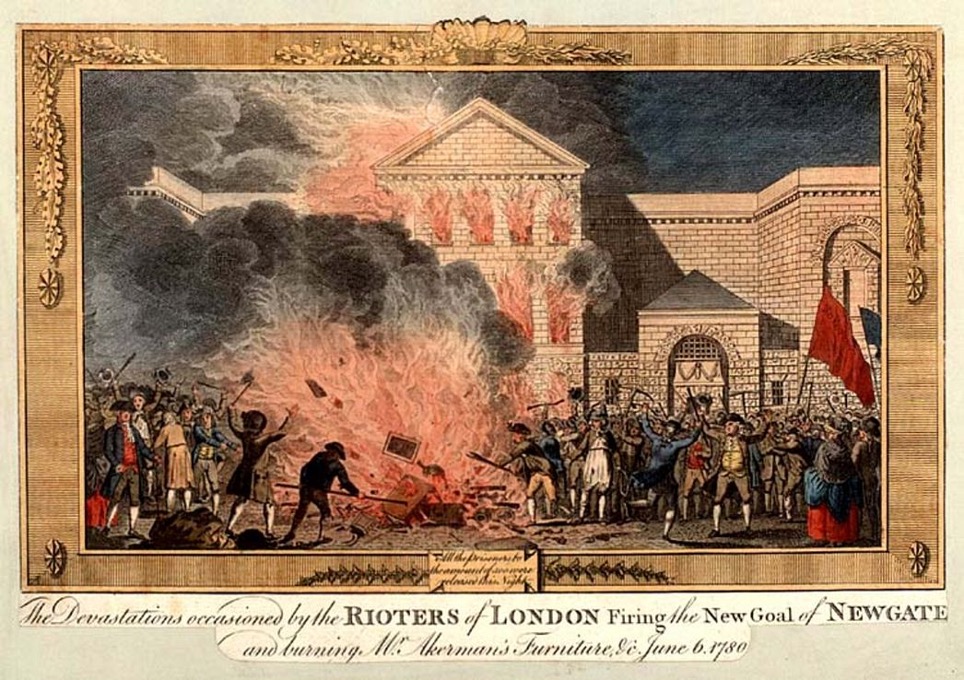

How did Catholic families in Essex fare? The 4th Lord Petre, living during the Commonwealth, was immediately suspected of being a Royalist, and by 1659 his liabilities exceeded his income by 20 times! Some others kept a very low profile and went ‘underground’, the most obvious example being the so-called priests’ hiding places. The Waldegrave family remained staunchly Catholic until 1721 when James Waldegrave took the Oath of Supremacy and found himself created Earl Waldegrave. But generally, with far fewer Catholic families in Essex (in 1634 only 20 of the 280 arms-bearing families) anti-Catholic legislation was only half-heartedly enforced. During the 18th century anti-Catholic rules were being relaxed; some Catholics entered the professions and, despite the flare-up of anti-Catholic riots in James II’s reign such as the Gordon riots, Catholicism was not seen any more as a threat to the state. Eventually, senior lay Catholics under the chairmanship of the 9th Lord Petre promoted a resettlement of the law, leading to the Act of Toleration and, eventually in 1829, the Emancipation Act.

Dr Amanda Flather, Women and the Reformation in Essex: Campaigns against religious change in Essex in the 1630s and 1640s.

Using evidence from church court records, together with diaries and wills, her paper focused on women’s involvement in local conflicts over religion in the decades before the Civil War. The 1630s was characterised by deep divisions within the church and state; the marriage of Charles I to a Catholic queen was seen as a threat to the Protestant nation, only exacerbated by the introduction by Archbishop William Laud of liturgical practices that placed a renewed emphasis on ceremony and sacrament. These changes were seen by zealous Protestants as a challenge to the customary order of worship to a dangerous degree, and Amanda examined how often women were involved in campaigns against Laudian policy.

Women, particularly married women, played a significant role in church services and parish life, including baptisms, as midwives, churching, funerals, church cleaning and washing of vestments, and they wielded considerable informal influence over the politics of the parish especially relating to moral issues. Women protested against Laudian changes to the liturgy, in particular over the conduct and form of ceremonies with which they were most closely associated such as baptism, burial and churching, which zealous Protestants regarded as ‘dangerously superstitious.’ Examples of resistance included refusal to wear the veil or to go to the altar rail to be churched. Tabitha Sharp of Sandon refused to be churched at all.

Clergymen were criticised by female parishioners for poor preaching and some women participated in campaigns by Parliament to root out ‘scandalous’ ministers. [See Graham’s talk, below]. Moral order was the aspect of parish politics in which female influence was dominant. The evidence suggests that married women of ‘middling’ status in particular were engaged in direct action to rescue their churches from what they saw as the clutches of popery. It is in the responses to Laudianism that allow us to trace female voices and opinions that are so rarely heard.

Sir Graham Hart : ‘Scandalous Ministers’? Parliament’s Persecution of the Clergy of Essex, 1644.

In 1644 the Civil War was still in the balance. Parliament controlled London, Essex and neighbouring counties, while the King’s forces controlled much of the North and West of England. Religion lay at the root of many of Parliament’s grievances against Charles I. In the 1630s he had supported Archbishop Laud’s hostility to Puritans and policies on ceremony in worship: Parliament was now reversing those policies and reforming the Church.

In January 1644 Parliament ordered the Earl of Manchester, the General of its forces in the Eastern Counties, to carry out a purge of the clergy within his area, which included Essex. The aim was to remove ‘scandalous’ ministers from the Church and replace them by ‘godly preaching ministers’. Manchester appointed committees in each county to hear complaints about the clergy, who could be ejected if judged unfit, and have their income from the parish confiscated.This opportunity for discontented parishioners to complain resulted in 39 ministers being referred to the Essex committees for scandalous ministers.

How did the parishioners interpret their remit to identify ‘scandalous’ ministers? The charges they brought fall into four groups. Seven of the ministers were pluralists who were accused of being absent from and neglecting their parish. A second group, more numerous, were accused of immorality. 19 ministers faced charges relating to drinking. Three or four of them appear to have had a serious drink problem: Simon Lynch, Rector of Runwell, even turned up at his hearing with the committee under the influence. Five ministers were accused of sexual offences, usually by women who claimed to be victims. Other behaviour unacceptable to some parishioners included mild swearing (‘by my faith and troth’) and playing cards.

A third group of charges accused ministers of having, in the 1630s, complied with instructions from the Bishop about religious matters, such as requiring parishioners to kneel at the rail before the altar to receive communion, or to bow at the name of Jesus. Such practices reeked, to puritans, of superstition, idolatry and popery.

A fourth set of charges related to acts which amounted to openly supporting the King in his conflict with Parliament. Parliament was particularly concerned about clergy who spoke against it, for example to persuade people to refuse to take the various oaths supporting its policies which Parliament tried to impose on them.

In summary a few of our Essex ‘scandalous’ ministers were, if the charges are accepted as truthful, unworthy to serve as parish ministers. But the great majority were not men of bad character. Instead, they seem to have been respectable ministers who were accused of failing to support Parliament in its conflict with the King, and of being on the wrong side in the puritans’ long struggle against the leadership of the Church of England.

Dr James Bettley: The Architectural Consequences of the Reformation in Essex

The Reformation was a turning point in the history of the country’s buildings just as it was for religious worship. The Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII, the suppression of chantries and guilds in 1548 under Edward VI and changes in liturgy resulted in the total or partial demolition of many existing buildings (Stratford Abbey, Barking Abbey, for example) and the adaptation of those that remained to new uses (Leez Priory, Walden Abbey. St. Osyth) and forms of worship, with the adaptation of parts of monastic churches to parochial use (such as Waltham Abbey, Little Dunmow, Blackmore, Tilty). Other structures were built or (partially) re-built out of monastic materials, such as Bourne Mill (Colchester) and Rochford Hall.

Many smaller buildings effectively became redundant, including parish guildhalls, although some, such as Finchingfield’s, continue to operate as community buildings. New institutions were founded to replace facilities previously associated with monasteries and chantries, notably almshouses (such as at Ingatestone, Felsted and St Mark’s College at Audley End) and schools, such as Felsted, Brentwood and King Edward VI’s grammar school at Chelmsford. In the 19th century many schools were refounded, but built in the Elizabethan or Tudor Gothic style. An example is the Royal Grammar School at Colchester (1852–3). Many almshouses were also rebuilt in the 19th century in a neo-16th style.

The Reformation had resulted in the alteration of church interiors almost beyond recognition, with removal of rood screens, statues, stained glass and wall paintings, some of which have been restored in more recent times. And without the Reformation there would have been no Nonconformist chapels. On the other hand, some of the newly rich in the later 16th century were building their great houses influenced by the latest fashions from the Continent, indicating that foreign influence continued in spite of the religious separation from Roman Catholic Europe.

But it is also true to say that so great was the enduring influence of the Reformation on our architectural heritage that many buildings continued to be designed in the style of the mid–16th century for the following 400 years.